This session on early lifecycle information opened with a focus on the crucial role of address and street data in the early stages of property development. The panel featured several industry experts, each bringing unique insights into the application and management of early lifecycle data.

Recordings of the 2025 conference talks can be found here

SPEAKERS:

- Chair: Steve Brandwood, Executive Director of Engagement, GeoPlace

- Mike Rose, with the Ministry of Housing, Communities, and Local Government

- Hannah Parker, Chief Product Officer, Addland

- Jack Ricketts from MadeTech

- Steve Taylor, Strategic Lead, National Fire Chiefs Council

In setting the context, Steve Brandwood explained recent initiatives undertaken by GeoPlace around lifecycle information, specifically the redesign of data entry conventions to better support address custodians. He noted the significance of capturing three critical stages of property lifecycle: planning application approval, building control notification, and completion notices. These stages ensure accurate tracking and management of properties from approval through to occupancy.

Additionally, efforts to integrate Unique Property Reference Numbers (UPRNs) into building control processes were highlighted, including collaboration with major organisations such as NHBC. Such integration facilitates greater consistency and reliability in data management, potentially bridging existing gaps between local authorities and building control entities.

Mike Rose, with the Ministry of Housing, Communities, and Local Government

Mike Rose then spoke on the importance of robust data standards in the planning application process. Mike, who has extensive experience with government data, notably from his roles at the Environment Agency and DEFRA, emphasised the need to understand data as more than merely technical infrastructure. He likened the importance of data standards to the trust placed in drinking water quality—while we may not individually verify standards, we rely heavily on established benchmarks to ensure reliability.

Mike is currently involved with MHCLG’s digital planning programme, designed to improve planning outcomes through better data management. This initiative aims for faster and more efficient planning decisions, enhanced community engagement, and streamlined plan-making. Central to achieving these goals is the consistent application of data standards, particularly at the submission stage of planning applications.

To illustrate the need for standardised data, Mike highlighted existing inconsistencies—such as site addresses being absent from one of the 24 standard planning application forms on gov.uk. His team is systematically addressing these gaps by breaking down current forms into modular data components and reassembling them into comprehensive data specifications. These specifications will be integrated into existing digital systems, ensuring that all data submitted is consistent, accurate, and compliant with national standards.

The ultimate goal, Mike explained, is seamless interoperability across planning applications, enabling local authorities to easily generate reports and share reliable data with MHCLG. He stressed the importance of open collaboration, inviting feedback from technology providers, local authorities, and other stakeholders to refine these standards further.

"Start at the start, but know where the finish is," Mike concluded, emphasising that understanding the initial data requirements and end-user needs will ensure the planning system benefits all involved.

Hannah Parker, Chief Product Officer, Addland

Hannah Parker, CPO of Addland, took the stage to spotlight one of the most overlooked yet impactful aspects of the property data ecosystem: usability. She began by reinforcing a theme already emerging in earlier sessions — that everything starts with great data — but argued persuasively that its value hinges on how effectively it’s translated into actionable, accessible tools.

Addland, she explained, is a data platform built to serve the entire real estate ecosystem, spanning public and private sectors and reaching down to everyday users — “your mum and dad,” as Hannah put it. Processing five terabytes of geospatial data weekly, the company deals with information volumes on par with Netflix’s entire catalogue, updated every seven days. But such scale, she warned, can create as many problems as it solves if not managed well.

“We're all wrestling with siloed systems, inconsistent formats, and clunky interfaces,” she said. Poor data translation leads to cognitive overload, decision paralysis, and ultimately distrust — a recurring frustration for those navigating planning systems or searching for accurate property information.

She cited a relatable example: the iPhone's often confusing "Location Services" warning. "That's data," she said, "but it's surfaced in a way that creates panic, not insight." Now scale that confusion to complex planning systems or property platforms — the risk of inaction or error multiplies quickly.

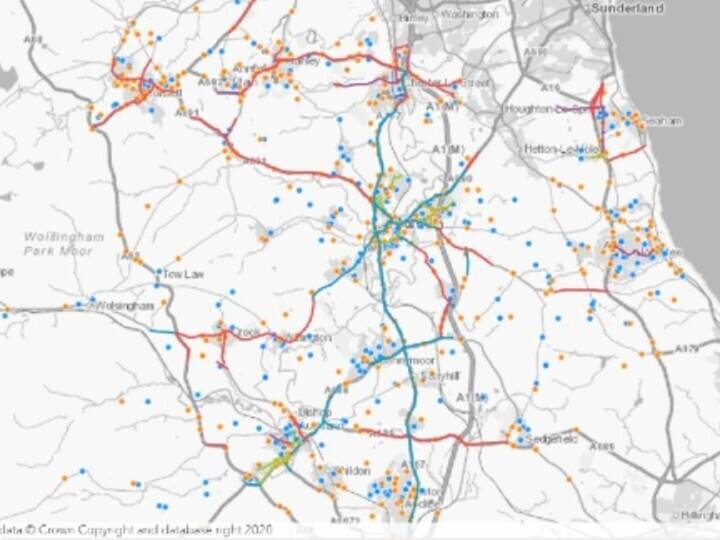

Addland’s solution, Hannah explained, lies in a map-based, user-centric platform offering advanced geospatial tools. Their system allows interactive exploration of any plot of land or property, combining planning, title, boundary, environmental, and sales data into a single accessible interface. “It’s immersive desktop analysis,” she said, capable of delivering centimetre-level accuracy — critical, for example, when assessing proximity to flood zones or ancient woodlands.

A cornerstone of Addland’s offering is its GIS research hub, which unifies multiple datasets and presents them in intuitive formats. Users can generate detailed, branded reports within minutes, or access over 100 data points from a single— a valuable asset for estate agents, landowners, planners and developers.

Addland also supports data access through APIs, catering to users who prefer to integrate data into their own platforms. These APIs cover common pain points like address cleansing (ensuring “Sarah’s House” is still recognisable as “1 High Street”) and emerging compliance challenges such as material information standards. Their ‘Considerations API’ even enables precision risk assessments for protected zones or environmental constraints.

Hannah then turned to a powerful real-world case study: a partnership with UK local authorities to overhaul the public’s experience of planning portals. “Everyone’s seen how wildly inconsistent they can be,” she said. Some portals are excellent. Others are “terrible” — difficult to navigate, inaccessible, and alienating for communities. Addland responded by creating a new collaborative tool, enabling the public to view, explore and comment on planning applications in a seamless, user-friendly interface. Though currently in stealth mode, the system is live and available to councils today, with a playbook ready for adoption.

More than just a technical exercise, Hannah underscored that Addland’s mission is grounded in human-centred design. “UX and accessibility should be non-negotiable,” she said. “If a human being is going to use your platform, you need to challenge your own assumptions and make sure it’s truly accessible.”

She closed with a reminder that smart design and inclusive data services are not just good ethics — they’re good strategy. “Set your standards early,” she urged. “If you do, you’ll bridge the gap between complexity and usability — and make data not just usable, but enjoyable.”

Jack Ricketts, Senior Product Manager, MadeTech

Jack Ricketts, Senior Product Manager at MadeTech and a former planning officer, opened with a simple but striking admission: during his time in local government, he was frequently asked two key questions — and couldn't answer either. "Is this home really affordable housing?" solicitors would ask. Or: “How many affordable homes actually exist in the borough?” Despite being responsible for tracking housing delivery, Jack explained that the core issue wasn’t access — it was absence. The data simply didn’t exist.

At the heart of this problem, he said, is a longstanding disconnect between planning and building control data. “There’s never really been a way to draw a clear thread from a planning application, through its amendments, to the specific homes that are eventually built on site,” he noted. Without that link, it’s near impossible to assess whether the right homes are being delivered in the right places — or even to count them accurately.

Jack described how the UK currently estimates housing delivery: through a fragmented patchwork of manual reports. Local authorities and private sector building control bodies must submit various returns (PS1/PS2, P2, AIR, CORE, LARS) multiple times a year, often duplicating effort. “None of these datasets are connected,” he said, “and they’re prone to human error.” To tackle this, MadeTech worked with planning and building control teams, the Planning Portal, and GeoPlace to test a new approach. Instead of counting houses retrospectively and relying on manual reporting, what if we tracked every home from the moment it was proposed?

The result was a prototype system that builds an end-to-end audit trail for each individual home, from planning application through to construction and completion. It allows developers, planning authorities, and building control bodies to view and update progress in real-time, including start and finish dates and any changes to plans along the way.

At the centre of the system is the UPRN, which acts as a consistent identifier for each plot or dwelling. By tagging all planning and building control records with UPRNs, the prototype makes it possible to break down silos, link disparate data sources, and automate reporting. "UPRNs are crucial," Jack stressed. They allow central government, local authorities, and even PropTech companies to share a common view of each property’s journey — without disrupting existing workflows. “If you’re not counting homes, how do you know how close you are to delivering the 1.5 million target?” he asked.

The prototype’s API also enables integration with third-party platforms and services — from sales values to council tax, building safety records, and energy performance certificates. Crucially, it provides a foundation for emerging AI and PropTech tools. “AI can’t deliver value if it’s built on duff data,” he warned. Jack drew a comparison with Transport for London’s open data policy, which catalysed a flourishing ecosystem of journey-planning apps. Similarly, by exposing accurate, timely property data through open APIs tagged to UPRNs, the housing sector could unlock a wave of smarter, faster, more transformational services.

Looking ahead, Jack announced that MadeTech and partners would be submitting this prototype to the Geovation PropTech Challenge in the coming month. Collaborators include local authorities such as Barnet, Doncaster, and Camden; national bodies like GeoPlace and the Home Builders Federation; private sector firms including BYI Planning Consultancy, ViewCity, and CaSH. “Fingers crossed,” he said in closing. “And hopefully we’ll be back to share what comes next.”

Steve Taylor, National Fire Chiefs Council

Now Strategic Lead at the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC), Steve’s journey into the world of fire safety began not in uniform but behind a desk — as a young IT worker in a local council, accidentally thrown into street naming and numbering. It was only when a manager explained that inaccurate addresses could cost lives that his job became something more. “That moment turned it into a calling,” he said. Years later, as head of Information Services at Essex County Fire and Rescue, Steve ensured that addressing data was treated as the vital asset it is. Today, working nationally with all UK Fire and Rescue Services, he continues to champion the importance of accurate location data — not only for emergency response, but increasingly for prevention and protection.

“Everyone thinks of the fire engine arriving with blue lights,” he said. “But most of what we do now is about preventing fires in the first place, and ensuring buildings are safe long before an incident occurs.” This involves two major areas. First, prevention: supporting vulnerable people with home safety visits. Second, protection: the fire service’s statutory duty to inspect non-domestic buildings — like this very conference venue — to ensure public safety.

“You just assume you’ll be safe in a place like this,” he said. “And rightly so. But it’s our job to make sure of it.” And yet, he pointed out, many fire services still struggle to answer a basic question: where are the tall buildings? Or care homes? Or hospitals? The reason isn’t a lack of intent — it’s a lack of clear, complete, and classified address data. “It should be easy,” Steve said. “But it isn’t, because the information isn’t always there. Or it’s wrong. Or it’s incomplete.”

Steve urged custodians of local address data and Street Naming and Numbering Officers to recognise the significance of their work. Accurate UPRNs assigned early and consistently across a building’s lifecycle, are crucial. Especially for multi-occupancy buildings, the fire service needs not just flat-level UPRNs, but a parent UPRN that represents the structure as a whole — because their responsibility is to the building, not the individual units inside.

Steve also highlighted the value of getting this data as early as possible, ideally from the moment planning permission is granted. “We’re statutory consultees on planning applications,” he said. “But we can’t fulfil our role if we don’t know what’s coming.” He praised GeoPlace’s work to improve parent–child UPRN classification and called on councils to do more, particularly in reducing the number of properties marked vaguely as “C” (commercial) without further detail. “If it’s a care home or a hospital, and you’ve just marked it as ‘C’, we won’t know it’s there. And if we don’t know it’s there, we won’t inspect it.”

To illustrate the real-world consequences, Steve shared a personal story. In January, his own home — a two-year-old house on a new estate — caught fire due to a faulty washer-dryer. Thanks to accurate address data, crews arrived within minutes. “It was the longest few minutes of my life,” he said. “But they saved the house.” He contrasted this with the frustrations of delivery drivers — and potentially emergency responders — who can’t find addresses on newer estates because of outdated maps or incomplete data. “I’ve literally had to get in my car and guide food delivery drivers to my door,” he said. “And those are services using live maps. So what happens in a real emergency?”

Steve closing remarks were both an appeal and a tribute. He asked local authorities to tighten classifications, assign UPRNs early, and understand the life-saving potential of their data. “The addressing work you do has become absolutely vital,” he said. “You may not realise it, but you’ve probably saved someone’s life. So thank you — you’re legends.”

Steve Brandwood then concluded the session by reinforcing the role accurate lifecycle data plays in broader governmental objectives, such as accurately tracking housing development progress toward national targets.