We all want a more planet-friendly, sustainable way of living, but the problem of practicality isn’t going away any time soon. Electric Vehicles (EV) are part of the answer to living a low carbon life, but how are we going to make that EV infrastructure work?

At COP26, global leaders agreed to accelerate the transition to 100% zero emission cars and vans. 2040 is the target date, but the UK government plans to phase-out the sale of new fossil-fuelled car and van sales by 2030. Ambitious, necessary, and challenging.

Almost 1 in 10 new cars are now totally electric. We have around 330,000 battery-operated vehicles in the UK, and the Tesla Model 3 was the UK's best-selling new car in September. In fact, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders reports growth of almost 90% in EV registrations, year on year – and with good reason. People like them. When I bought my car in 2014, a VW Golf, I had one eye on the future. I was driving perhaps 16,000 miles a year, and it's only been over the last 18 months that mileage has reduced, due to the pandemic. The car is ageing well but I will need to think about what to buy, soon.

An EV will make sense for me, my family, and, yes, for the planet – this is not a fad or a ‘tree-hugging’ statement of days gone by but questions such as ‘how will I charge it?’ and ‘how much will it cost me to own and run it’ still exist.

Sustainable transport is important. People I know and work with have abandoned the concept of car ownership altogether and use different modes of transport and associated charging models to satisfy their transport needs. The Transport Decarbonisation plan published by the DfT in July 2021 and the Net Zero Strategy published by BEIS in October 2021 talk about decarbonising all forms of transport and making public transport, cycling and walking the natural first choice for all who can take it with a £2bn investment over 5 years. This facilitates choice in how we travel, shop and use our leisure time in our local neighbourhoods and areas without the use of a car.

In the RAC’s 2021 report on motoring, 82% of respondents said they’d find it difficult to live without a car, a higher proportion than ever before. There’s a greater dependency on personal vehicles now, even though we’re doing fewer commuter journeys. 71% said they use their car for commuting instead of alternatives because it’s quicker, with just over half (55%) saying there are no feasible public transport options. 42% of drivers aged 17-24 said they’ll use their cars more in the future as a result of the pandemic.

This is a real challenge for government departments and local authorities. They carry the burden of putting the practical plans in place that will help the UK to reduce its current emissions by 78% in 2035 and to achieve Net Zero by 2050. Not surprisingly, 300 local authorities (60% across unitary, metropolitan and county authority types) have now declared a climate emergency.

The focus on ‘finding answers’ has never been greater: the question is, ‘where do we find the missing piece in the EV puzzle?’

10% of all global emissions are related to road Transport and rising faster than any other sector https://ukcop26.org/transport/

Do we have enough EV charge points?

No, we don’t. Government statistics, tell us there are just over 24,000 public EV chargers available in the UK (excluding charging points installed in people’s homes).

Some UK local authorities have UK Government funding to install more, and the Office for Zero Emission Vehicles’ (OZEV) On Street Residential Chargepoint Scheme provides a grant to part-fund (75%) the capital costs of buying and installing on-street charging points – there are also grant schemes for installing EV chargers in the home and workplace, and grants towards buying a new vehicle.

In the DfT’ and OZEVs ‘Transitioning to zero emission cars and vans: 2035 delivery plan’ there are strong commitments to accelerating EV infrastructure, too. The plans promise to enable:

- the creation of a Local EV Infrastructure Fund, a £90m fund to support larger on-street charging schemes and rapid charging hubs across England

- the publication of an EV Infrastructure Strategy and regulation for infrastructure provision in new homes later this year.

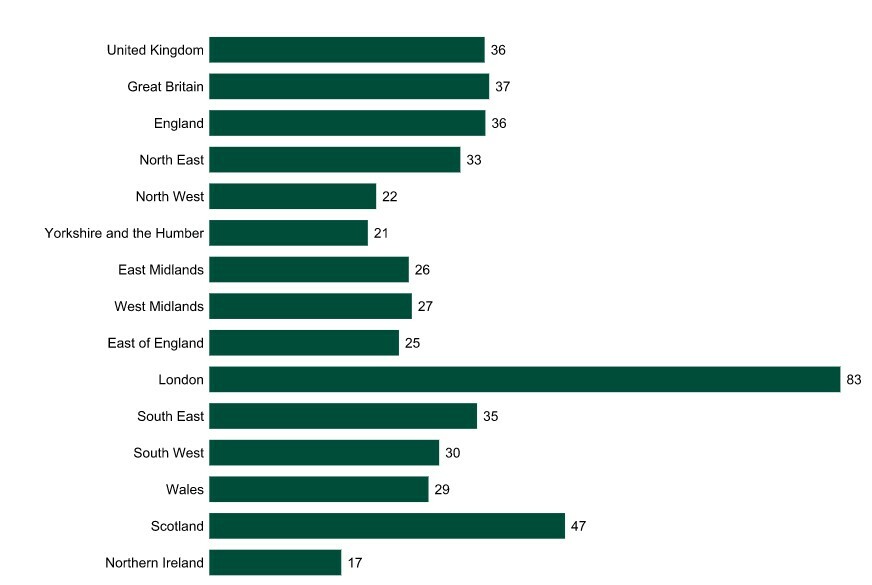

But it’s not enough. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published a study that suggests at least 280,000 to 480,000 public charge points will be needed by 2030 – more than 10 times the current number (around 25,000). The distribution of charging devices is currently uneven, and if we are to meet the targets set – then we do need to support and find better ways to facilitate the adoption of EVs, and the rollout of more EV infrastructure, countrywide.

The role of local authorities and the energy sector

The CMA report also focussed on the role of local authorities in this rollout. It said, “local authorities in Great Britain have a key gatekeeper role as they are responsible for parking and street furniture like lampposts where on-street charging is often installed… … but while there are some examples of good practice, we found that generally, local authorities do not have any plans in place, dedicated personnel, financial resources or in some cases the appetite to drive forward roll-out.”

Part of the challenge is that, while the understanding may be authority-wide, local authorities per se do not have a clearly defined role. The provision of EV charging is not a statutory duty. This means it can be a lower priority, and still is in many cases.

In response to a request from the Environmental Audit Committee, the National Audit Office produced a report that considered how effectively central government and local authorities in England are collaborating, to clarify local authorities’ role and look at the resources and skills needed, to reach those net zero targets.

In short, local authorities need a mandate. They need guidance to facilitate the rollout of EV infrastructure within their communities. It’s been really encouraging to see that the Government’s press release in the last week stating that new homes and buildings such as supermarkets and workplaces, as well as those undergoing major renovation, will be required to install electric vehicle charge points from next year. There’s still more to do.

The Energy Saving Trust has resources that will help, and the Local Government Support Programme is also available. Ofgem, too, also has an important role to play in enabling this rollout and the widespread adoption of EVs. The ‘Enabling the transition to electric vehicles: the regulator's priorities for a green, fair future’ document describes the regulator’s priority activities – but there is still more to do.

If we’re going to reach those ambitious targets, then we need systemic adaptations to our infrastructure, a consistent and cohesive link between the public, local authorities, central government, energy networks, electricity suppliers and the regulator. And all this collaborative effort must be coupled with an educational programme that changes our behaviour.

Location data is the key

To ensure EV infrastructure is rolled out faster, better, and more efficiently we need to use location to answer all of these questions, and more:

- Where is there a consumer demand for electric vehicles?

- Does that demand need to be met by public infrastructure – or private?

- Do EV owners have access to private charge points on their driveways?

- Where are the car parks, which properties have driveways?

- Which buildings are listed – where will we have conflicts of interest?

- Which streets are private streets, where do councils’ responsibilities end?

- Which streets would be suitable for a residential charge point scheme?

Location data exists today that tells us where EV charge points exist but this is provided by third parties and may not be to a defined standard, openly available or have the currency, accuracy or coverage of the data required. This is something that the DfT are looking at with the Data Discovery on Open EV chargepoint data they awarded earlier in the year and I’m looking forward to the outcomes and recommendations of this activity.

I also have hopes that the forthcoming EV Infrastructure Strategy addresses challenges in making even more data accessible, available and interoperable to help answer those questions above but that it will go one step further and a) support the creation, management, and maintenance of core EV infrastructure data that doesn’t exist today and b) set the ball rolling for a local authority EV mandate notwithstanding that there are wider questions that also need to be answered:

- What is the impact of the physical and data infrastructure on local authorities? On data/asset management and streetworks coordination?

- How will congestion be affected, while this EV infrastructure is being installed?

- How will people plan for charging en route – and will those chargers all be available and working?

- Where might gaps in EV infrastructure be, how will communities be affected?

- Irrespective of EV infrastructure, can the energy network support the extra needs or is there work to do in specific business and/or geographic areas?

- How can we enable the flow of energy, transport and payment data to electricity suppliers and their customers to enable a positive consumer experience in paying to charge their vehicle or to sell energy back to the grid?

Location data is the missing piece in the EV puzzle

Location data provides the means to connect the myriad different suppliers, processes, systems and organisations that need to answer fundamental questions about rolling out EV infrastructure.

The Unique Street Reference Number (USRN) and Unique Property Reference Number (UPRN), now available under Open Government Licence (OGL) let us find the answers by connecting data and systems in a way that stimulates innovation, creates efficiencies and meets policy objectives.

We blogged recently about UPRNs being essential in shaping policy for on-street EV chargers, particularly for people living in flats, or who don’t have off-street parking.

Check out the report from OS, which recently ran a 2-day hackathon for collaborators to work on ways to enhance EV infrastructure in Britain, and its case study on the use of OS AddressBase® for planning EV charge points across the UK.

If you’re already using USRNs and UPRNs to answer questions about EV infrastructure and EV demand or would like to explore how USRNs and UPRNs could help, then please get in touch.